Contents

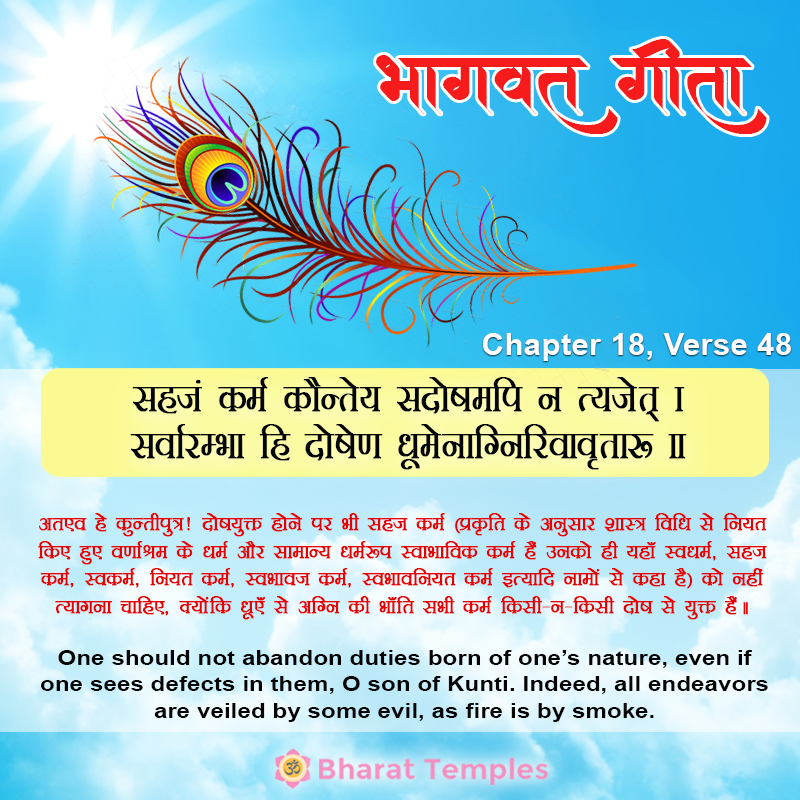

सहजं कर्म कौन्तेय सदोषमपि न त्यजेत् |

सर्वारम्भा हि दोषेण धूमेनाग्निरिवावृता: ||

saha-jaṁ karma kaunteya sa-doṣham api na tyajet

sarvārambhā hi doṣheṇa dhūmenāgnir ivāvṛitāḥ

भावार्थ:

अतएव हे कुन्तीपुत्र! दोषयुक्त होने पर भी सहज कर्म (प्रकृति के अनुसार शास्त्र विधि से नियत किए हुए वर्णाश्रम के धर्म और सामान्य धर्मरूप स्वाभाविक कर्म हैं उनको ही यहाँ स्वधर्म, सहज कर्म, स्वकर्म, नियत कर्म, स्वभावज कर्म, स्वभावनियत कर्म इत्यादि नामों से कहा है) को नहीं त्यागना चाहिए, क्योंकि धूएँ से अग्नि की भाँति सभी कर्म किसी-न-किसी दोष से युक्त हैं॥48॥

Translation

One should not abandon duties born of one’s nature, even if one sees defects in them, O son of Kunti. Indeed, all endeavors are veiled by some evil, as fire is by smoke.

English Translation Of Sri Shankaracharya’s Sanskrit Commentary By Swami Gambirananda

18.48 Kaunteya, O son of Kunti; na tyajet, one should not give up;-what?-the karma, duty; sahajam, to which one is born, which devolves from the very birth; api, even though; it be sadosam, faulty, consisting as it is of the three gunas. Hi, for; sarva-arambhah, all undertakings (-whatever are begun are arambhah, i.e. ‘all actions’, according to the context-), being constituted by the three gunas (-here, the fact of being constituted by the three gunas is the cause-); are avrtah, surrounded; dosena, with evil; iva, as;; agnih, fire; is dhumena, with smoke, which comes into being concurrently.

One does not get freed from evil by giving up the duty to which one is born-called one’s own duty-, even though (he may be) fulfilling somody else’s duty. Another’s duty, too, is fraught with fear. The meaning is: Since action cannot be totally given up by an unelightened person, therefore he should not relinish it.

Opponent: Well, is it that one should not abandon action because it cannot be given up completely, or is it because evil [Evil resulting from discarding daily obligatory duties.] follows from the giving up of the duty to which one is born?

Counter-objection: What follows from this?

Opponent: If it be that the duty to which one is born should not be renounced because it is impossible to relinish it totally, then the conclusion that can be arrived at is that complete renunciation (of duty) is surely meritorious!

Counter-objection: Truly so. But, may it not be that total relinishment is itself an impossibility? Is a person ever-changeful like the gunas of the Sankhyas, or is it that action itself is the agent, as it is in the case of the momentary five [Rupa (from), vedana (feeling), vijnana (momentary consciousness), sanjna (notion), samskara (mental impressions)-these have only momentary existence. In their case there can be no distinction between action and agent, simply due to the fact of their being momentary.] forms of mundane consciousness propounded by the Buddhists? In either case there can be no complete renunciation of action.

Then there is also a third standpoint (as held by the Vaisesikas): When a thing acts it is active, and inactive when that very thing does not act. If this be the case here, it is possible to entirely give up actions. But the speciality of the third point of view is that a thing is not ever-changing, nor is action itself the agent. What then? A nonexistent action originates in an existing thing, and an existing action gets destroyed. The thing-in-itself continues to exist along with its power (to act), and that itself is the agent. This is what the followers of Kanada say. [Their view is that agentship consists in ‘possessing the power to act’, not in being the substratum of action.] What is wrong with this point of view.

Vedantin: The defect indeed lies in this that, this veiw is not in accord with the Lord’s view.

Objection: How is this known?

Vedantin: Since the Lord as said, ‘Of the unreal there is no being৷৷.,’ etc. (2.16). The view of the followers of Kanada is, indeed, this that the non-existent becomes existent, and the existent becomes nonexistent.

Objection: What defect can there be if it be that this view, even though not the view of the Lord, yet conforms to reason?

Vedantin: The answer is: This is surely faulty since it contradicts all valid evidence.

Objection: How?

Vedantin: As to this, if things like a dvyanuka (dyad of two anus, atoms) be absolutely nonexistent before origination, and after origination continue for a little while, and again become absolutely non-existent, then, in that acase, the existent which was verily nonexistent comes into being, [Here Ast. adds, ‘sadeva asattvam apadyate, that which is verily existent becomes nonexistent’.-Tr.] a non-entity becomes an entity, and an entity becomes a non-entity! If this be the view, then the non-enity that is to take birth is comparable to the horns of a hare before it is born, and it comes into being with the help of what are called material (inherent), non-mateial (non-inherent) and efficient causes. But it cannot be said that nonexistence has origination in this way, or that it depends on some cause, since this is not seen in the case of nonexistent things like horns of a hare, etc. If such things as pot etc. which are being produced be of the nature of (potentially) existing things, then it can be accepted that they originate by depending on some cause which merely manifests them. [According to Vedanta, before origination a thing, e.g. a pot, remains latent in its material cause, clay for instance, with its name and form unexpressed, and it depends on other causes for the manifestation of name and form.] Moreover, if the nonexistent becomes existent, and the existent becomes non-existent, then nobody will have any faith while dealing with any of the means of valid knowledge objects of such knowledge, because the conviction will be lacking that the existent is existent and the nonexistent is nonexistent!

Further, when they speak of origination, they (the Viasesikas) hold that such a thing as a dvyanuka (dyad) comes to have relationship with its own (material) causes (the two atoms) and existence, and that it is nonexistent before origination; but later on, depending on the operation of its own causes, it becomes connected with its own causes, viz the atoms, as also with existence, through the inherent (or inseparable) relationship called samavaya. After becoming connected, it becomes an existent thing by its inherent relationship with its causes. [The effect (dyad) has inherent relationship with existence after its material causes (the two atoms) come into association.]

It has to be stated in this regard as to how the nonexistent can have an existent as its cuase, or have relationship with anything. For nobody can establish through any valid means of knowledge that a son of a barren woman can have any existence or relationship or cause.

Vaisesika: Is it not that relationship of a non-existent thing is not at all established by the Vaisesikas? Indeed, what is said by them is that only existent entities like dvyanuka etc. have the relationship in the form of samavaya with their own causes.

Vedantin: No, for it is not admitted (by them) that anything has existence before the (samavaya) relationship (occurs). It is surely not held by the Vaisesikas that a pot etc. have any existence before the potter, (his) stick, wheel, etc. start functioning. Nor do they admit that clay itself takes the shape of a pot etc. As a result, it has to be admitted (by them) as the last aternative that nonexistence itself has some relationship!

Vaisesika: Well, it is not contradictory even for a nonexistent thing to have the relationship in the form of inherence.

Vedantin: No, because this is not seen in the case of a son of a barren woman etc. If the antecedent nonexistence (prag-abhava) of the pot etc. alone comes into a relationship with its own (material) cause, but not so the nonexistence of the son of a barren woman etc. though as nonexistence both are the same, then the distinction between the (two) nonexistences has to be explained. Through such descriptions ( of abhava, nonexistence) as nonexistence of one, nonexistence of two, nonexistence of all, antecedent nonexistence, nonexistence after destruction, mutual nonexistence and absolute non-existence, nobody can show any distinction (as regards nonexistence itself)! There being no distinction, (therefore, to say that:) ‘it is only the “antecedent nonexistence” of the pot which takes the form of the pot through the (action of) the potter and others, and comes into a relationship with the existing pot-halves which are its own (material) causes and becomes fit for all empirical processes [Such as production, destruction, etc.] but the “nonexistence after destruction” of that very pot does not do so, though it, too, is nonexistence. Hence, the “nonexistence after destruction”, etc. [Etc. stands for ‘mutual nonexistence (anyonya-abhava)’ and ‘absolute nonexistence (atyanta-abhava)’.] are not fit for any empirical processes, whereas only the “antecedent nonexistence” of things called dvyanuka etc. is fit for such empirical processes as origination etc.’-all this is incongruous, since as nonexistence it is indistinguishable, as are ‘absolute nonexistence’ and ‘nonexistence after destruction’.

Vaisesika: Well, it is not at all said by us that the ‘antecedent nonexistence’ becomes existent.

Vedantin: In that case, the existent itself becomes existent , as for instance, a pot’s becoming a pot, or a cloth’s becoming a cloth. This, too, like nonexistence becoming existent, goes against valid evidence.

Even the theory of transformation held by the Sankhyas does not differ from the standpoint of the Vaisesikas, since they believe in the origination of some new attribute [i.e. in the origination of a transformation that did not exist before.] and its destruction. Even if manifestation and disappearance of anything be accepted, yet there will be contradiction with valid means of knowledge as before in the explanation of existence or nonexistence of manifestation and disappearance. Hery is also refuted the idea that origination etc. (of an effect) are merely particular states of its cuase. As thelast alternative, it is only the one entity called Existence that is imagined variously through ignorance to be possessed of the states of origination, destruction, etc. like an actor (on a stage). This veiw of the Lord has been stated in the verse, ‘Of the unreal there is no being৷৷.’ (2.16). For, the idea of existence is constant, while the others are inconstant.

Objection: If the Self be immutable, then how does the ‘renunciation of all actions’ become illogical?

Vedantin: If the adjuncts (i.e. body and organs) be real or imagined through ignorance, in either case, action, which is their attribute, is surely superimposed on the Self through ignorance. From this point of view it has been said that an unenlightened person is incapable of totally renouncing actions even for a moment (cf. 3.5). The enlightened person, on the other hand, can indeed totally renounce actions when ignorance has been dispelled through Illumination; for it is illogical that there can (then) remain any trace of what has been superimposed through ignorance. Indeed, no trace remains of the two moons, etc. superimposed by the vision affected by (the disease called) Timira when the desease is cured.

This being so, the utterance, ‘having given up all actions mentally’ (5.13), etc. as also, ‘Being devoted to his own duty’ (45) and ‘A human being achieves ‘success by adoring Him through his own duties (46), becomes justifiable.

What was verily spoken of as the success arising from Karma (-yoga), characterized as the fitness for steadfastness in Knowledge,-the fruit of that (fitness), characterized as ‘steadfastness in Knowledge’ consisting in the perfection in the form of the state of one (i.e. a monk) free from duties, has to be stated. Hence the (following) verse is begun: